A Cruel Man Delighting in Flowers

...the mildness to which men ... had yielded was only half of the intoxication of beauty, while the other half ... was of such surpassing and terrible cruelty—the most cruel of men delights himself with a flower—that beauty ... failed quickly of its effect...

Hermann Broch, The Death of Virgil

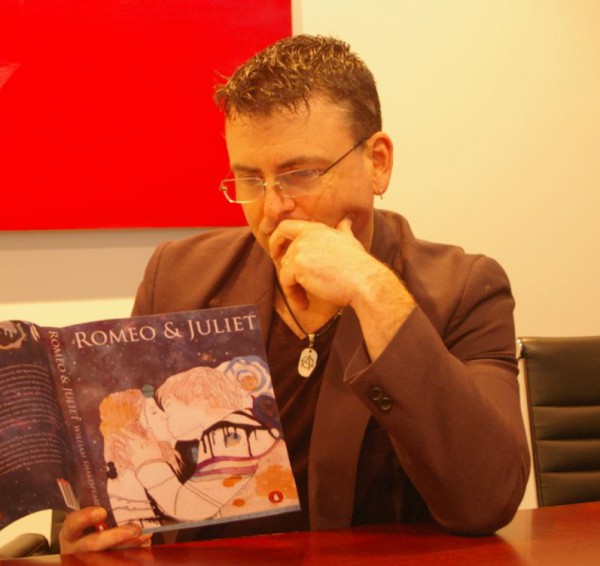

Jeremy Davies is made of ink, but don’t dip a feather in him. It tickles. He once painted a fingernail black and no one really noticed. He was disappointed. He’s also an editor, a religious atheist, a liker of strong coffees, a Shakespeare-lover, a political anarchist and someone who rarely has a pen when he needs one. He has been a PhD candidate, a personal trainer, a life model, a bouncer, an infantry soldier and someone who rarely had a pen when he needed one. He has had words published in a variety of places, in a variety of publications, in a variety of forms, in a variety of moments: Canada, Wet Ink, SMS and twelve minutes past three in the afternoon being some of these. His first novel, 'Missing Presumed Undead', will be re-published by Satalyte Publishing in February 2014. A second is on its way.

Camusian Essays

This book is a book of books and bits and pieces, so impossible really to review closely in one hit. So, I plan to review each independent part separately as I finish them and adjust the star counter as necessary.

The first Lyrical Essay ‘The Wrong Side and the Right Side’ (L’Envers et L’Endroit). FIVE STARS

If, in spite of so many efforts to create a language and bring myths to life, I never manage to rewrite The Wrong Side and the Right Side, I shall have achieved nothing.

Preface, 1958

First published in 1937 in a very limited print run, Camus’ first work is a Lyrical Essay in parts. The 1958 preface to its republication in his Nobel year is full of recognisable quotes, particularly on the art and craft of writing; a topic he takes up with some gusto, since he had been refusing to have this book republished due to his artistic ‘vanity’. Words he uses to describe his own writing include ‘awkward’, ‘pompous’ and ‘clumsy’. But, he also writes:

...there is more love in these awkward pages than all those that have followed.

The Essay is in five parts: Irony, Between Yes and No, Death in the Soul, Love of Life, and The Wrong Side and the Right Side. In a broad, Camusian thematic sense, looking back from the privileged knowledge of where his thought will go, we move from how meaning shifts; what life is considering this instability; Despair; Love; and, finally, what this means for being human in the sense of moral engagement. I am going to mostly focus on the development of Camus' ideas, but take the 'Lyrical' part of the idea of the 'Essay' for granted as absolutely and fundamentally successful, even in translation, obviously; such a powerful mode of writing for Camus, so energetic and languid at the same time in its astonishing beauty and knife-keen ability to cut open moments, places, people and ideas all at once.

‘Irony’ brings together three character studies, and none of them fit together.

A woman you leave behind to go to the movies, an old man to whom you stop listening, a death that redeems nothing, and then, on the other hand, the whole radiance of the world. Here are three destines, different and yet alike. Death for us all, but his own death to each.

And herein lies the irony that Camus explores through his lyrical mode—and the sentences, even when thick with despair, have the kind of drenching light-and-dark beauty of a Caravaggio squeezed into ink. It’s the additional meaning to all meaning, that there is both meaning in meaninglessness, and in reverse. This is the basis of existential estrangement. It is the birthplace of that thing he will one day call the Absurd.

The final of the three character sketches—the death that redeems nothing—is also heavily autobiographical in nature, based on his overbearing grandmother in Algiers, and how she ruled.

‘Between Yes and No’ could be read as a prequel to L’Etranger (The Stranger/The Outsider). Here is Meursault while his mother was alive, and his approach to life still being formulated in his mind.

...I recall not a moment of past happiness but a feeling of strangeness.

In the face of estrangement, pre-Meursault grapples with the idea of affirming the act of living or negating it. Negation is more attractive...

There is a dangerous virtue in the word simplicity. And tonight I can understand a man wanting to die because nothing matters anymore when one sees through life completely.

But affirmation becomes almost a demand of him through experience...

Since this hour is like a pause between yes and no, I leave hope or disgust with life for another time. Yes, only to capture the transparency and simplicity of paradises lost—in an image. ...the feeling that the whole absurd simplicity of the world has sought refuge here.

...and finishes with a position that appears to dovetail nicely with the Meursault as we know him from L’Etranger:

...what wells up in me is not the hope of better days but a serene and primitive indifference to everything and to myself.

‘Death in the Soul’ was based on Camus’ own trip to Prague, and is a precursor to ‘A Happy Death’—which in turn was a precursor to ‘L’Etranger’, so once again, there are shades of Meursault, though this unnamed protagonist is far more involved and introspective, and reminded me of Dostoevsky’s protagonist from ‘Notes from Underground’. Travel narrative is now used as a motif to investigate estrangement; our protagonist is struck by his inability to exist in Prague, where even the elements conspire against him.

I visited churches, palaces and museums, tried to soften my distress in every work of art. A classic dodge: I wanted my rebellion to melt into melancholy. But in vain. As soon as I came out, I was a stranger again.

So religion, politics and art only obfuscate and distract him momentarily. He can be reading the instructions on the shaving cream he has already been using for a month while someone is dead next door. But then a move from Prague to Vicenza in Italy seems to make all the difference. He is happy, but he cannot shake the sense of longing and loss: ‘...a mystery hangs in the sky from which beauty and indifference descend.’

It was and yet was not the anguish I had felt in Prague.

He recognises that nothing has essentially changed, just as with the churches, palaces and museums; here is another firmament: nature itself, he is still Undergound.

...the confrontation between my deep despair and the secret indifference of one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world.

Camus has written ‘Love of Life’ before ‘The Death of the Soul’, but chose to place it after in the publication, maybe because it begins in a more sublime mode, albeit more in the milieu of humanity than nature. Now we’re in Palma, Spain; another travel narrative, the overt stranger in a strange land, but now a reveler, albeit a thoughtful one, of course... The protagonist moves from humanity out into nature, and there is further dramatization of the central project: ratifying an absurd brokenness between what is apparent and what simply is.

If the languages of these countries harmonized with what echoed deeply within me, it was not because it answered my questions but because it made them superfluous. ...this Nada whose birth is possible only at the sight of landscapes crushed by the sun. There is no love of life without despair of life.

We embrace loving as mode for living, something that is so abstract and ridiculously human, but then, we always end up thirsty, despite it. We are still bound by concrete.

Finally, a conclusive chapter of the same title as the book itself, and the shortest at only four pages long.

...why wonder if something is dying or if men suffer, since everything is written on this window where the sun sheds its plenty as a greeting to my pity?

We fall down into truth, and awareness; to live between sides, to gaze just as squarely at the light as at its opposition, whether that is the dark or death. The tension exists, so, in the parlance of our times, Camus says: deal with it. You are wrong, and you are right.

One man contemplates and another digs his grave: how can we separate them? Men and their absurdity? But here is the smile of the heavens. The light swells and soon it will be summer. But here are the eyes and the voices of those I must love. I hold onto the world with every gesture, to men with all my gratitude and pity. I do not want to choose between the right and the wrong sides of the world, and I do not like a choice to be made.

After all, I am not sure that I am right.

2014 ... my year of Franzen

On the strength of all this twitterverse/op-ed bullshit now being written about Jonathan Franzen, I will now be declaring 2014 my 'Year of Franzen' ... which basically just means I am committing to actually reading one of his books. I mean, for a 'white male writer' (a common pejorative phrase, until you become a 'dead' one...) is the only thing worse than a really bad review, a really good one?

Moby Dick and the Absurd: A Camusian Reading

It is scarcely easier to describe in a few pages a work that has the tumultuous dimensions of the oceans where it was born than to summarize the Bible or condense Shakespeare.

Albert Camus, ‘Herman Melville’, Lyrical and Critical Essays

I begin with this quote for two reasons: it’s absolutely true, and: I decided to read this book based on my Camus Centenary reading rule of alternating between a Camus-authored book and a Camus-related book. However, this was a long voyage, perhaps appropriately… On the high seas, I was within these pages over three months, due to a distinct lack of pleasure-reading time. But it was worth it. Majesty, pure majesty in every way, and in a way that does make one think of the Old Testament and Shakespeare. I reread sentences, paragraphs, sometimes whole pages, just for the sheer pleasure of the words, how they sounded in my head, how they sounded out loud, how they ‘meant’ to me, how they ‘meant’ to my ideas. Due to the sheer magnitude of this book, I am happy to limit my response here to a very Camus-based reading, and look at it through the prism of his ideas. Otherwise, I could be caught up for another three months or so just writing a review.

In the same short essay, Camus goes on to say that the book represents…

...one of the most overwhelming myths ever invented on the subject of the struggle of man against evil, depicting the irresistible logic that finally leads the just man to take up arms first against creation and the creator, then against his fellows and against himself.

So Camus wants us to consider this book as a moral tale, whereby there is a tension between what is ‘good’ or ‘right’ and what is ‘evil’ (not ‘bad’ or ‘wrong’, but ‘evil’), and that through the pursuit of directly struggling against ‘evil’ (not trying to do what’s ‘good’ or ‘right’, but opposing ‘evil’ itself) there is a fall into destructive behaviour, including, finally, self-destruction.

We are introduced to the world of Moby-Dick through a narrator, Ishmael; the pseudo-author who has quite a philosophical bent. He sets up his ideas on humanity and the world he occupies early on, waxing lyrical:

…the meaning of that story of Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.

But it’s too late to make any improvements now. The universe is finished; the copestone is on, and the chips were carted off a million years ago.

There is certainly a bleakness being established here, and a sense of the Absurd, whereby the universe is not providing for us the meaning we desire from it. And already a taste of self-destruction on page three with the mobilizing of the myth of Narcissus in this way. But is there any hope?

But Faith, like a jackal, feeds among the tombs, and even from these dead doubts she gathers her most vital hope.

And the Preacher in the pulpit sets up the idea of ‘evil’, that being something that is purely bad, even on a spiritual plane, something that is inherently against Grand Meaning…

“Jonah did the Almighty’s bidding. And what was that, shipmates? To preach the Truth in the face of Falsehood! That was it!”

and

“Woe to him who would not be true, even though to be false were salvation!”

And while Ishmael is hardly the Bible-thumper, and often expresses an antipathy towards Christian thought, he is very concerned with the idea of Truth and Meaning. He has a kind of Naturalist bent in his thoughts, something Camus also explored in his early work, like in ‘Summer in Algiers’. Ishmael, ever-the ironic reflector, reflects:

But, perhaps, to be true philosophers, we mortals should not be conscious of so living and so striving.

and

It is not down on any map; true places never are.

And eventually comes to a conclusion which echoes the idea of the brokenness of the human condition in the Absurd:

…and Heaven have mercy on us all—Presbyterians and Pagans alike—for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending.

Then we are introduced to Ahab, who is the real protagonist, slowly. He’s a ghost for quite some time. Just stories are told, as if he is some kind of mythic figure, the man who will be true, even if to be false would mean salvation, the man who is mad enough to fight something that is un-fightable, who demands too much. He becomes no longer human, a superhuman? A god? Which is of course too much.

He’s a grand, ungodly, god-like man, Captain Ahab…

But there is something left in him.

No, no, my lad; stricken, blasted, if he be, Ahab has his humanities.

Finally, he emerges, but only days after the Pequod has left harbour, and they are well away from land.

…but moody stricken Ahab stood before them with a crucifixion in his face; in all the nameless regal overbearing dignity of some mighty woe.

And, of course, the antagonist, the white whale, Moby Dick. He too is told about through stories, and emerges physically only much later. Starbuck and Stubb play pivotal roles in the Camusian reading of this book: Starbuck is reason, Stubb is sans-reason; Starbuck is the humanist and for humanity and unity and brotherhood, Stubb is the nihilist, for the pursuit of whatever he can get from this meaningless void of the universe. Early on, Starbuck is made uncomfortable by Ahab’s quest, Stubb is only uncomfortable by how is personally treated, but works through that. In arguing with Starbuck, Ahab sets out his model of the Whale, it’s Meaning:

“All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. … If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate.”

So here is the ‘evil’, and the ‘evil’ is established with a certain Platonic Truth/Forms sort of flare.

…all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified and made practically assailable in Moby Dick.

So is he crazy to think that Moby Dick is ‘all evil … visibly personified’? Or is he crazy to think that such a thing, even if it was, could ever be ‘practically assailable’? Both, would be my Absurd suggestion. Ishmael thinks differently:

God help thee, old man…

he worries

…thy thoughts have created a creature in thee; and he whose intense thinking thus makes him a Prometheus; a vulture feeds upon his heart for ever; that vulture the very creature he creates.

But this is previous to him whaling. The more he whales, the more Ishmael seems to almost disappear into the story. He is hardly even present in the Epilogue as the survivor. Is it him? If it is him, he does not sound the same.

We find in them [Melville’s oeuvre] revolt and acceptance, unconquerable and endless love, the passion for beauty, language of the highest order—in short, genius.

Albert Camus, ‘Herman Melville’, Lyrical and Critical Essays

Ishmael turns savage, and rebel.

I myself am a savage, owning no allegiance but to the King of the Cannibals; and ready at any moment to rebel against him.

And herein, he begins to establish the patterning of the Camusian Absurd Hero; but, unlike Ahab, he sees in the whale (the whale generally, not the White One necessarily…) the very model of this.

Oh man! admire and model thyself after the whale! … Do thou, too, live in this world without being of it.

and

…see the omniscient gods oblivious of suffering man; and man, though idiotic, and knowing not what he does, yet full of the sweet things of love and gratitude

And Ahab, in response to the ‘omens’ of destruction as he nears the end of the quest, spits at them, in a very Macbethian way.

“I now know thee, thou clean spirit, and I now know that thy right worship is defiance.”

This is a different variety of rebellion though to Ishmael’s. It is the rebellion of the hero who is aware but refuses. Ahab’s madness begins to be sullied by fraternal thoughts, interestingly brought on through the psychologically damaged Pip, ‘like curing like’; but through this Ahab begins to question himself and his relentless pursuit of the whale, the wall between him and Truth. Is it worth it. He begins to recognise the roles Stubb and Starbuck are playing:

Ye two are the opposite poles of one thing; Starbuck is Stubb reversed, and Stubb is Starbuck; and ye two are all mankind.

And he begins to favour the Starbuckian idea of mesure, eschewing the Stubbian All-or-Nothing zeal when he is rallying the men for the attack on the White Whale:

”D’ye feel brave men, brave?”

“As fearless fire,” cried Stubb.

“and as mechanical,” muttered Ahab.

Despite Starbuck’s temptation to murder Ahab—and, in fact, maybe because of it—under Starbuck’s influence he is almost ready to abandon the quest…

But, in the end, Ahab has come too far. Starbuck is not enough. He collapses, a little like how Hamlet collapses when he considers the fate of man and the fall of a sparrow:

“Ahab is forever Ahab, man. This whole act’s immutably decreed. ’Twas rehearsed by thee and me a billion years before this ocean called. Fool! I am the Fates Lieutenant; I act under orders.”

And he acknowledges his collapse and failure in the face of the Absurd. Starbuck, like Stubb, isn’t even aware of the Absurd, as Ahab is, but Ahab’s failure is his inability to live in the tension, as Ishmael has.

“Close! Stand close to me, Starbuck; let me look into a human eye; it is better than to gaze into sea or sky; better than to gaze upon God.”

…or Truth. Ahab is aware enough to acknowledge that it is the humanist/Starbuckian that is missing for him.

“…but Ahab never thinks; he only feels, feels, feels.”

He tries to save Starbuck, but he will not save himself. He demands the annihilation of Truth. And his final act before the final chase is an act of Starbuckian fraternity to Starbuck.

I am old; shake hands with me, man.

And he dies the death of a criminal. The Truth sentences him, as he knew it would. As it had to. Otherwise, it would stop being.

To separate myself very briefly from the Camusian reading, I wanted to express my thrill and appreciation for the two chapters that quite obviously paid homage to the exchanges between Hamlet and the Gravedigger, with Ahab and the Carpenter stepping forward for the roles. I'll finish by briefly quoting a part of one of these, which uses some neat irony and heavy punning to play with a kind of Camusian principle that I haven't really touched on here…

[Carpenter]“Faith, sir, I’ve——”

[Ahab]“Faith? What’s that?”

[Carpenter]“Why, faith, sir, it’s only a sort of exclamation-like—that’s all, sir.”

[Ahab]“Um, um; go on.”

Clamence: the Insider ... and the Fall

In any case, I only like confessions nowadays, and the authors of confessions write chiefly in order not to confess, saying nothing of what they know. When they pretend to be owning up, that’s the moment to beware: they’re putting make-up on the corpse.

As far as his prose-fiction output goes, Camus is most well-known for three works: L'Étranger (The Outsider or The Stranger), The Plague and this one, The Fall. The first two have definitive places among cycles of his work within his oeuvre and the development of his ideas: the Absurd and Revolt respectively. But the The Fall does not. It wasn't even part of the planned third cycle—Love—that was never completed due to Camus’ accidental death. It was a short story that grew into a novella, and was published separately to the other short stories that were put together as Exile and the Kingdom.

Let me firstly say that, of the three theatrical versions of Camus’ work that I have witnessed, it is Drew Tingwell’s performance as Jean-Baptiste Clamence, in Michael Cronin’s adapted-for-the-stage version of this book, that has most occupied a Camus protagonist for me during my rereading of his work this year. I could visualize him delivering some of the key lines, like:

But let me introduce myself: Jean-Baptiste Clamence, at your service. Delighted to meet you. You must be in business? More or less? Excellent reply. Judicious too: we’re only more or less in anything.

Maybe because it is so suitable for a one-man-show? I mean, as a novel, it is a one man show… Anyway, he seems to occupy Clamence for me now in a way that the actors who played Meursault and Rieux do not.

This novella is a confession, and a confession about the nature of confessions and what they mean. How they work for us. Why they’re necessary. What makes someone guilty, what makes someone innocent, in a specific and a general sense. Clamence adopts the role of Judge-penitent, a role he does not explain completely until the very end of the story. We, the reader, the nameless companion in the bar and streets and houses of Amsterdam, occupy the role of hearing the confession of this fallen man. And he pokes us along at a pretty brisk rate, often teasing us with information that is still-to-come.

We follow his progression as a lawyer defending those who need to be, but always on ‘the right side’. He is beyond reproach, and he enjoys this position immensely… To be above, looking down. But an event occurs, mirroring, very gently, an event that occurred in Camus’ life, that causes a breakdown in the character of Clamence, a questioning of himself, a sense of guilt that was always there, that should always have been there, but he had resisted. And he feels the judgement of all around him. He regularly hears phantom laughter that comes from nowhere.

Later, talking about Jesus, he finds room to condemn Him as guilty, even before he’s born. No lamb, He…

And then he went away forever, leaving them to judge and condemn, with a pardon on their lips and a sentence in their hearts.

In some ways, as Robin Buss’s introduction touches on nicely, Camus is responding to the Paris intellectuals who froze him out over his inconsistent politics … inconsistent in the sense that Camus wasn’t ever happy to accept any manifesto as unquestionable blueprint for Life. This novella is his response, an appropriately literary response that assaults his ‘enemies’, while at the same time does not absolve himself.

Bistro atheists?

And while this is an interesting historical and biographical point, Camus reaches much further. You can easily cast contemporary roles for the ‘bistro atheists’ he talks about.

They’re free, so they have to get by as best they can; and since, most of all, they don’t want any freedom, or sentences, they pray to have their knuckles rapped, they invent dreadful rules and they rush to build pyres to replace churches

Camus is an atheist, but, he cannot so easily jettison the depth of moral consideration and conviction of Christian theology … not when he mistrusts the purposes and ‘paydays’ of what is offered in replacement, and Clamence expresses some of that, but always with apology.

In short, you see, the main idea is not to be free any longer, but to repent and obey a greater knave than you are.

If Meursault is the Outsider, then Clamence is the Insider. The Outsider ascends to death on innocence, the Insider falls to life in guilt.

Aren’t we all the same, continually talking, addressing no-one, constantly raising the same questions, even though we know the answers before we start?

Clamence is the man for our times. He is our Janus, the kind we worship. He would be a celebrity now, not a lawyer, but an actor playing a lawyer on a major HBO big-budget series, the kind people talk about at water coolers and on Facebook pages. And the charitable works he would perform! You would see all on his Twitterfeed. Our age would have sustained him far longer than the 50s could…

Some mornings, I would conduct my trial to the very end and reach the conclusion that what I excelled in above all was contempt. The very people I most often helped were those I most despised.

Twisted Tales II: Out of Time

Hey, I can get away with marking it on the strength of the other contributors without looking like I'm just spruiking my own work ... right? It's a good read for science/speculative fiction readers and just good ol' short story readers generally. The Double Dragon Publishing link http://www.double-dragon-ebooks.com/single.php?ISBN=1-55404-450-2 contains an excerpt from my humble contribution: 'Martian Colours' ... don't let that turn you off though...

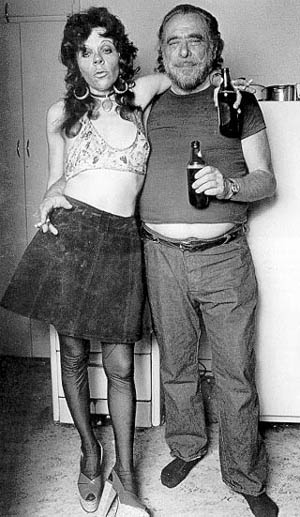

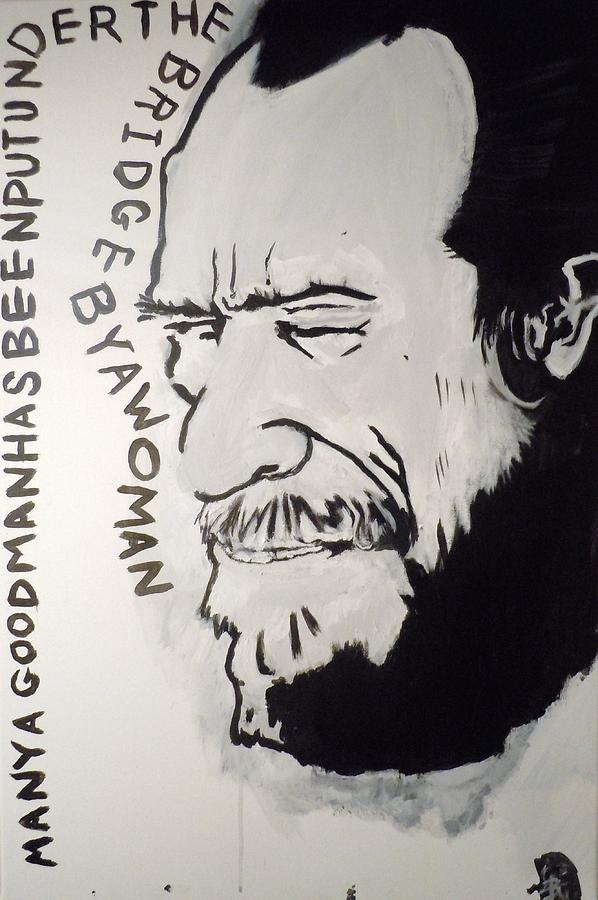

Bukowski and Women ... In the Face of No Chance at All

Bukowski is a five star poet writing a three star story, averaging out to four stars: but with a +1/2 star for pure, unmixed vodkaric fucking artistic courage … if you’ll pardon the bland but necessary tautology. Instead of a Nobel Prize, a Purple Heart and a Medal of Honor should have been meted out to him. When Chinaski—Bukowski’s fictionalized self—is asked about the kinds of writers he likes, the attribute he mentions about them is their bravery. He’s asked: why?

“Why? It makes me feel good. It’s a matter of style in the face of no chance at all.”

And that’s what he is.

The declarations and codifications of his writing seem to baffle him. The misos or the isms. He’s aware of them. But he goes on. You can beat him up. You can run him down. You can trash his typewriter in the middle of the road. He not only takes his chances, he understands them. They are nil.

"What do you think of women?" she asked.

"I'm not a thinker..."

Chinaski seems to be aware of the vanishing-point that is the saturation of hate-ideology, and in the face of it, he places himself, not with any Saint George-like ideal of conquering it, but at least if he can just…be…him… that’s style in the face of no chance at all. That is courage. Once they have absorbed the entire avenue of discourse open to the writer, then ‘fuck them’ becomes all that you have to at least bridge between the body of it all and your own yawp.

Love … is like trying to carry a full garbage can on your back over a rushing river of piss

Love was for guitar players, Catholics and chess freaks.

For Chinaski, the other side of bravery is love. Not in an antonymic sense, but it is the sense, the device, the object by which you fall into something that becomes too great to have courage through. This is why he often expresses awe in its face, because it is the one thing that can really defeat him. He expresses pity for those who he encounters who seem to be under it, he expresses self-pity for the one time in the past when he was also so afflicted. He avoids women who have men who love them.

Maybe I should have slammed her? How did a man know what to do? Generally, I decided, it was better to wait, if you had any feeling for the individual. If you hated her right off, it was better to fuck her right off; if you didn’t, it was better to wait, then fuck her and hate her later on.

Chinaski is an absurd hero. He is fully aware of the absurdity of his condition in the story, and regularly expresses complete bafflement for how he is making a living as a poet, and how these women are appearing in his life … and what they’re prepared to do for him. But he still takes what is given freely, and he gives freely. He undergoes ordeals that would have me in a homicidal fit of rage, and yet he can go berserk if the music is too loud; a woman can all but kill him in the street, but he will still help them move house; he is contradictory, obtuse, will-full, forgiving, passionate and reserved, destructive and self-destructive, creative and lacking-in-imagination. He is one of us, one of the losers; cast as a winner. He celebrates his winnings, but is humble enough to remain a loser.

"I never pump up my vulgarity. I wait for it to arrive on its own terms."

Which brings me to his three-star-ish-ness. I take notes while I read for future reference, along with a page number, and this kind of tells the story. Normally, the gems I unearth are pretty evenly spread out page number wise. With this book, there would be forty, fifty page gaps; and then a series of notes over one, two or three pages. It’s as though Bukowski has a series of great poetic works of character insight, and he strings them together to create a book.

"I write. But mostly I take photographs."

...he admits, jokingly, but it also rings true. He’s joined a series of fascinating shots together. It’s certainly well worth the read, as a tonic for our only-for-fun or moral-prescriptive emphasis on reading now fashionable.

What a rush to stumble upon a poet who is not a sociologist, who is not an organ-grinder, who is his own monkey.

This book won’t make you a better person, or a better citizen. It will make you more human ... more or less; it will equip you better for your own silence; it will sheath your soul more comfortably, because it will further develop that discomfort and anxiety that is the very definition of the human soul. And that is the object of literature.

"You write a lot about women."

"I know. I wonder sometimes what I’ll write about after that."

"Maybe it won’t stop."

"Everything stops."

Ink for Ink: 'The Word Made Flesh'

A birthday present from my mother, suggested by my eldest sister who knew I was planning on adding to my skin a literary tattoo in the near future: I have loved ones and physical interests currently represented, but no literary...

Some great work here, the Kafka sleeves (although I shall be going for something a little more subtle...) and some of the interpretive artwork, fantastic. Some of the stories behind the tattoos were good, some okay, some bordering on total wank ... but that's okay. Exegesis often leaves me cold.

The weirdness of having really flash-in-the-pan pop fiction, like Twilight or even Harry Potter, permanently afixed to your skin though... Questionable. Some people here are complaining in their reviews about the material being to 'heavy' but, I mean, a) it does say 'Literary' in the title and b) you better be pretty sure you have something other than a passing individual connection with a phrase or an image before you get it tapped in.

My first literary tattoo shall be from 'Hamlet', but not this one:

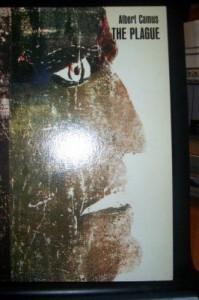

Fellowship with the Defeated: Camus' 'The Plague'

1913–2013 A hundred years of Albert Camus, a writer.

…and to state quite simply what we learn in a time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.

Yes, Nazism influenced the writing of this story, Camus was living through it and resisting it, in his way; but it is not about it. This novel, published after The Myth of Sisyphus and written during the sometimes hostile response to the book, begins what became to be known as Camus’ ‘Cycle of Revolt’ (along with The Rebel and the plays L'état de siege and Les justes). It is of interest to note that one of the regular complaints regarding Camus’ series of essays (notice, I do not say ‘Book of Philosophy’, which he never did…) of The Myth of Sisyphus—by both Camus’ contemporaries and thinkers today—is that it is ‘too abstract’ to be taken as a serious philosophical tract. The journalist, Rambert, echoes them when he says to Doctor Rieux:

”You’re using the language of reason, not of the heart; you live in a world of … of abstractions.”

In response, Rieux later muses to himself:

Yes, an element of abstraction, of a divorce from reality, entered into such calamities. Still, when abstraction sets to killing you, you’ve got to get busy with it.

In this story, a city in North Africa, Oran, where Camus had lived for short amounts of time, becomes quarantined due to an outbreak of bubonic and, later, pneumonic, plague. Lots of people are dying and everybody has to deal with it, in their way. We follow the responses most closely of a Doctor (Rieux), a journalist (Rambert), a writer (Grand), an intellectual … for want of a better word (Tarrou), a priest (Paneloux) and a criminal (Cottard). Also of note is ‘the asthma patient’ that Rieux treats at key points in the narrative (in particular, right at the starts of the plague and right at the end. Why? Because his lung condition is mirroring Camus’ own (tuberculosis)—he required frequent treatments from Doctors, like Rieux—and it’s important to note that Camus’ often considered himself on the verge of death due to his condition, mirroring the psychology of those living with the plague: to live with the knowledge of the threat of imminent and unavoidable death.

‘They’re coming out, they’re coming out..’

He says gleefully. And later, at the end, he poses an important rhetorical question that’s been foreshadowed throughout the story:

”But what does that mean—‘plague’? Just life, no more than that.

And Tarrou, much later:

”…I had plague already, long before I came to this town.”

No, not Nazis, but life; but more specifically, life being brought into sharp focus, creating an awareness of it through an understanding that it ends. Being forced into exile by the plague, or not, the absurd conditions of life remain unaltered. It’s the awareness of the conditions that shifts through plague-caused exile: to be separated from the rest of the world, from love, from culture, etc; for it to be a part of your consciousness, and the consciousness of all the exiles around you, this is the plague. What does this do the people? It drives out Hope. It makes them live only in the past (through memories) and the present (through knowledge). The future no longer exists. Your illusions regarding your existence have flown. You have no peace.

This is the plague. The awareness of the absurd.

The only option is revolt; even in the face of the unchangeable.

And through this it’s possible, maybe not to be a saint, but to be a man.

…it was only right that those whose desires are limited to man, and his humble yet formidable love, should enter, if only now and again, into their reward.

How these characters come to terms with the plague and, thus, the Plague, forms the bulk of the story; and how they all, in different ways, follow Rieux’s lead and accept revolt, forms its chief intellectual interest. Without wanting to give away serious plot points, think about this when one of them contracts both varieties of plague—bubonic and pneumonic—the first person ever to do so…

Don’t get me wrong: this is also an aesthetic achievement of the highest order, even in translation: the scene with the dying boy reaches the aching terrible narrative beauty of one of Camus’ greatest literary heroes, Dostoevsky. But, indulge me in discussing some of these characters and how they played out in a kind of general sense, if you will…

Tarrou and Rieux have the most special relationship: the moment of ‘respite’ they share swimming alone at night in the forbidden sea is memorable to both of them, and to the reader. Just before hand, in conversation with Rieux, Tarrou comes to his main point about his life:

”It comes to this,” Tarrou said almost casually, “what interests me is learning how to become a saint.”

”But you don’t believe in God.”

”Exactly. Can one be a Saint without God?”

A little later on, Rieux finally responds:

”But, you know, I feel more fellowship with the defeated than the saints. Heroism and sanctity don’t really appeal to me, I imagine. What interests me is—being a man.”

”Yes, we’re both after the same thing, but I’m less ambitious."

Seeking sainthood is its own variety of retreat from the plague, not revolt. It’s full acknowledgement that the plague is greater-than. While Tarrou obsesses over existential issues, and broad morality, in his efforts to not transmit the plague to others, he can’t help but do so anyway.

Paneloux, the priest, and Rieux clash on the other side of the plague. When Paneloux is introduced into the story, it is early days in the plague: people are seeking the solace of the Church, and he delivers his First Sermon, which is your typical ‘this is God’s vengeance upon his misbehaving creation’ kind of fare. Rieux is unimpressed. However, he asks Paneloux to become involved in the Santization Groups and he accepts, throwing himself into the actions of the revolt against the plague. After the death of the boy scene, there is a shift in his beliefs, and his Second Sermon follows that event. For those who have read The Brothers Karamazov...

(if you have not, what are you doing reading this rubbish review? Stop it and go out and read this book instead… No, wait, there’s time, as long as you don’t have plague: finish my review first…)

...this sermon could be read as how Aloysha should have responded to Ivan Karamazov when the death of innocents was put toward him as a reason to revolt against God (Book V, Ch. IV). Rieux summarises Ivan’s position nicely:

”And until my dying day I shall refuse to love a scheme of things in which children are put to torture.”

Instead of Aloysha’s quiet wishy-washy acceptance (coupled with his refusing to face the outcome of this acceptance) … a little like modern Western Christianity generally … Paneloux responds:

”Believe everything so as not to be forced to deny everything.”

”…they must acquire and practice the greatest of all virtues: that of the All or Nothing.”

He’s not saying that you’re either for God or against Him, but that you’re either with God or without Him. It’s no good being with Him when without plague, and without when you are. Because then you are without him anyway.

Rambert is the lover who wants to run from the plague. But comes to his own absurd realization.

Cottard finds the plague-stricken world better than the normal world.

Grand, the writer, revolts with the rest of them, but his life remains disturbingly unaffected. He obsesses over his opening sentence, which he’s been working on for years, mirroring Camus’ obsession with his book, which took him longer to write than any other. When Rieux gets a look at the full manuscript Grand is working on he notices that:

The bulk of the writing consisted of the same sentence written again and again with small variants.

In the end, even during the victory celebrations, the plague’s there, laying dormant, never really gone, waiting, even on ‘the bookshelves.’

Read this book. Get the plague.

Talisman of Troy

If someone had've suggested to me, before reading this book, that an author could come along and successfully marry Homeric poetic style and atmosphere with contemporary ancient-historical fiction, I would've been skeptical, to say the least.

But this book does just that. A simply fantastic yarn that manages to cross a boundary into inspiring literature occasionally. Although I get the point of a previous reviewer regarding a pre-knowledge of Homer, I'm not sure it is a must. I think it certainly adds to the experience, but I'm pretty sure this book would stand alone.

The Manfredi/Manfredi author/translator combination is also worth pointing out: the translations of his older works have never been as strong. If you are reading Manfredi in English, check that the translator is Christine Manfredi.

Stop Eating Their Mother ... in 'Birthday Letters'

I love Hughes' work, but found the bulk of these poems so obviously personal that I had difficulty finding an 'in', as opposed to the bulk of Hughes' other work. There are, of course, great exceptions to this, and the one poem 'The Dogs are Eating Your Mother' is worth the entire book. Where, as Christina Patterson puts it in 'The Guardian': "For the first time, the quiet voice of the survivor was set against the high-pitched screams of those who claimed to represent the one silenced through suicide."

I have never been a Sylvia&Ted'ophile, and couldn't care less for all the chiefly gender-war/political responses to their personal relationship. There are few poets anymore in the way that Ted was—poets that are willing to place themselves in the crossfire—poets that aren't sociologists—so Ted's work is also powerful in this regard.

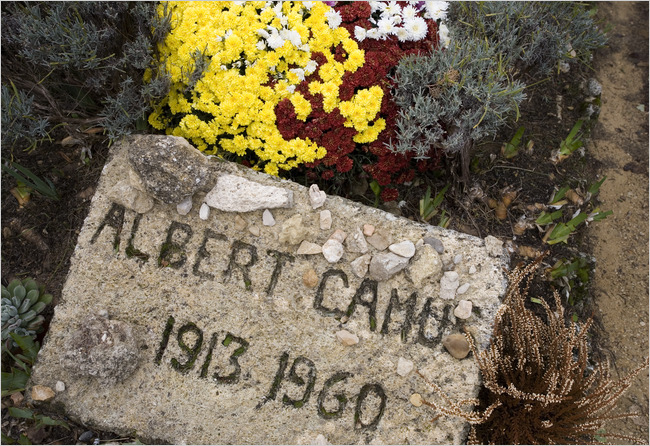

Man is Nothing Without Men: 'Camus, A Life'

Camus had often told friends that nothing is more scandalous than the death of a child, and nothing more absurd than to die in a car accident.

Narrative inevitability…

I am not a biography reader generally, and I try to avoid too much authorial back-story, and the variety of literary criticism that aggressively privileges the author’s ‘life-narrative’ (as it is pushed by another author or group of authors…) as a means for considering his work irritates me like wearing sandpaper inside your shoes. It’s unnecessary, even if it’s been cut and trimmed perfectly to the size of your feet, the result is the same. Sore feet and no real further understanding.

(And I gave this four stars, since to give it five would put it on the same level as the very works that brought me to this book in the first place.)

So why read it?

I wanted to know more about him.

Has it changed my appreciation of his oeuvre?

Perhaps, but not to any detriment: it has acted more as an emulsifier for the materials that were already bubbling around in my mind and my heart. There are echoes of Camus' stories in Todd’s story, and his research into Camus’ life through a whole range of sources is absolutely superb. Where it falls down, it only falls down due to lack of existing evidence. Camus was a very private man, and concerned about material that would be considered gold by future biographers. Todd had very few letters written back to Camus, due to his penchant for destroying such things, but, fortunately, the letters he sent to others were often preserved by them.

My particular historical area of interest is in Nazi-occupied Paris: a fantastically absurd, contradictory and dark period of that city’s life.

This…

…with this…

And this is an area where much of the information Todd works from is sketchy, due to the very nature of a) the secrecy involved in resisting the Nazis and b) the general cover-up of details post-Nazi period due to fear of being branded ‘collaborative’. I actually took extensive notes during these chapters, for my own reasons, and sometime they appeared contradictory… However, Todd still manages to string together a decent narrative through this fascinating period. There are beautiful details, like the gifting of the overcoat (that may just be the one) in the most iconic picture.

There’s him chatting with Sartre, a very serious intellectual, like any of us guys used to do about women in a bar, and how to best 'score'. There’s the Picasso play with a who’s who of artists of the period.

[Top row (left to right): Jacques Lacan, Cecile Eluard, Pierre Reverdy, Louis Leiris, Pablo Picasso, Fanie de Campan, Valentine Hugo, Simone de Beauvoir, Brassai

Bottom row: Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Michel Leiris, Jean Abier. Photo: Gilberte Brassai]

There’s references to proofreaders (one of my professional roles) and their general political leaning towards Anarchism (my own political leaning) which was nice after Henry Miller’s rather negative take on the profession; probably because Miller had to actually be one, while Camus was above them…

His structure is basically chronological, but his chapters are themed, so that there is some repetition and analepsis, but it’s not terribly jarring when it occurs. He quotes Camus well, from a range of different sources; and his friends—and enemies—on a range of topics: art, writing, philosophy and existentialism, politics (in particular, Colonialism and the ‘Algeria Question'), love, women, marriage, the nobility of humanity, and honour.

Nobility obliges one to honour, but being a man obliges one to nobility. Honour is a style of life … honour was the only possible morality for a man without God, as man’s reasons cannot stand by themselves; it is man who stands by himself in their place … Man is nothing without men.

Camus goes from poverty to education to journalism to creative writing to world-wide Nobel Prize level recognition. His message on receiving the Nobel to both his illiterate disabled mother and the teacher who pushed him to go further is so charged with feeling. When he comes to his apartment to make the announcement his first words to them are:

Life is a novel.

To which a friend replies:

Poor Albert—you would have made such a handsome marginal character.

Todd builds well to the inevitable denouement. Time starts getting shorter. Events come into sharper focus. My heart started beating harder. I wanted to read fast, like I wanted him to die quicker(?) We hear about every possible little detail, his basic little commentary to his secretary, everything, the last interview details, the last little letters to his various lovers, the last thing he said to his wife, his children, and it all seems so precious because we know what’s coming, it comes down to hours … minutes … and then all those little ironies that makes us believe in fate, the train ticket that he had that if he had taken would've avoided… The seat-switch to the front passenger side because he was shorter… All those stupid meaningless things that suddenly attain meaning because of the event.

Absurd.

Absurd in the event, absurd in our idea that our narration of the event makes any difference, that the idea of ‘chance’ exists, that any event that has happened had ‘a chance’ of not happening, that if it has happened it hasn't proved that if has a 100% chance of happening.

Absurd that we could think that this death is any more absurd than any other: that we live and that we don’t expect to die. And that death exists at all for the animal that is aware of it…

There is the absurd. I love the man, and all he stood for, even if I have some arguments with him; he appears to not be the kind of guy that demanded agreement: he demanded engagement and struggle and love. And he demanded some of these things too much, of both himself and the men and women around him.

I am also without God (since He doesn't present himself, despite my demand for Him), and without Kings (since I demand freedom over servitude), so like Camus, I must believe in men (with a wo- in front or not). This takes courage and a sense of the absurd. It’s much easier to believe in things that can’t really ever prove themselves.

'Legend' ... Formative Gritty Heroic Fantasy

I read this—Gemmell's first novel, and my first novel of his—many years ago, but it had a big impact on me. It brought me back to the genre of Fantasy—for a while, anyway—with his gritty brand of heroism. Some might argue that it is his most raw, and perhaps it is that rawness that makes it so grand. He is one of the few authors who I would buy the new release of without even thinking.

Anyway, It's certainly better than this whole new Martin-mania deal...

A Tropic Book, and the Demand of the Dead White Man...

The book is perhaps summed up best by one of its characters:

…I’ll lay myself down on the operating table and I’ll expose my whole guts … every goddamned thing. Has anyone ever done that before?—What the hell are you smiling at? Does it sound naïf?

It exposes. It hadn’t been done before (well, not in the same way). It is comic. It is naïf. It gives the growing legions of 'dead white men' haters plenty of ammo. Someone like Miller even loads the gun for them, and helps zero the sights.

With Henry Miller’s bizarre and incongruous existence in his time and place, there’s a kind of sense of loss, that something was lost after him, that an opportunity slipped us by. He represents a fork in the road, and it’s a fork that was never really taken. Instead, he can be easily reduced to a series of issue based identity-political dot points. Easily, that is, by those that…

…live among the hard facts of life, reality, as it is called. It is the reality of a swamp and they are the frogs who have nothing better to do than to croak. The more they croak the more real life becomes.

The same sort of people that can look at this book, even the first thirty pages or so, even if that’s all they read and threw the mouldy paperback down in disgust and reproach, and then croak on about ‘narcissism’, about ‘dead white men’, about ‘misogyny’ about all the stinking murky depths of the swamp that they’re paddling in.

So, all the croaking aside, what is Miller’s project? He takes Walt Whitman by the end of his beard and drags him along behind him through the streets of 1930s Paris and all the humanity around him, the world of men and women, and goes the full length, he starts with drums and ends with dynamite, he makes the world more endurable in his own sight, he throttles all the birds in creation, he tries to look earnest and looks pathetic, he finds himself again naked as a savage, he makes pages explode, he disregards existent principles, he contradicts and paralyzes, he makes lists of experience, he lives a life rendered down to cunts and stomachs.

This is not fifty shades of fucking grey. This is not a series of banal-titillations made to feel extreme and naughty while you keep warmly rolling in the swamp, wrapped up in a bunch of ideas that’ll keep you moist enough to pass inspection. There is no comfort here, unless it is the comfort of understanding that there is no comfort. Perhaps you have to be hungry and desperate to get to that point? You have to be that to make ‘the guinea pigs squeal’. To know where to put ‘the live wire of sex’, to know…

…that beneath the hard carapace of indifference there is concealed the ugly gash, the wound that never heals.

Is Miller above all this crap? Looking down like a Titan? If he’s part Titan, he’s also part goat. He’s below it. He’s burrowing underneath like he’s a haemorrhaging mole. You’re not meant to love him. Or like him. Or respect him. He asks for nothing from you. He doesn’t ask for you to review his book, since the book is a failure, it's not even a book, because it has to be a failure or else it fails completely; and since reviewing it is just further croaking in the every-spreading swamp of reality. Looking up a picture to slot into the coding so that someone might Like it and say, hey, yeah, nice review man, I liked that book too, lots of fucking, gave me a boner; or no, I disagree, this only got printed coz it gave guys boners and this book was a waste of my precious time when I could be reading the latest Miles Franklin shortlist from onetofive or something exceedingly more contemporary andslashor relevant, or that currently has a film version out with [insert some cunt] in it. I mean there’s only one review that counts and, bang-oh, you start writing the book out word-for-word in all its glorious lack-of-glory and all its primal failure that then bleeds into that time when you were living at the Villa Borghese, and maybe it wasn’t lice, and maybe it wasn’t cunt, or books or dreams you were asking from life, but there was shit happening that you might not want to put down on a piece of paper, since it would certainly be inappropriate and revealing even if you shook it really hard and laughed and covered it in irony since there’s actually nothing appropriate going on down there, under the carapace, where all you might need is to have a rosebush thrust under your nose.

walk4one

Being the editor of this book from an early stage, it feels difficult to review it ... I feel almost as close to it as the work I've written. Working with Sam on this has been one of my major professional experiences, and I believe it will remain so for some time.

Being the editor of this book from an early stage, it feels difficult to review it ... I feel almost as close to it as the work I've written. Working with Sam on this has been one of my major professional experiences, and I believe it will remain so for some time. It is an adventure/travel book, with a particular Christian faith-based spine running through it, but it is also a very human book, and certainly has a sense of the Quixotic about it at times. Sam does not shrink away from the tough questions, for others and also---most importantly---for himself, and he changes as both a man and as a man-of-faith from one cover to the other: even 'the walk' itself changes in what it stands for and how it 'means'. It's laugh-out-loud funny at times, and it's head-shaking sad at others.

Well worth a read, no matter your relationship with theism!

Poetry and Truth in 'A Happy Death'

‘No, because I’m constantly in revolt. That’s what’s wrong.’

At either end of his writing life, we have two fractured novels. The First Man was a genuinely unfinished work-in-progress at his time of death, whereas this novel, his first novel-in-embryo, was reworked a number of times before Camus abandoned it in favour of L'Etranger. And there are certainly similarities. Roger Quilliot has suggested that ‘Meursault [protagonist of L'Etranger] '…is the younger brother of Mersault [protagonist of this novel].’ And he was working on this between 1936–38, concurrently with the play Caligula and then moving away from it in 1939 and toward L'Etranger. And there are similar scenes and characters and tropes, mostly in Part One. Part Two differs in a number of ways, but thematically, parallels can be drawn with not-so-long bow strings. The Discussion between Mersualt and the Doctor, Bernard, towards the end reminded me of the even later The Plague for that matter…

Workshop of Camus' uncle in Algeria in 1920. Camus is

in the front, center, in a black smock.

But all this aside (points perhaps mostly of interest to those who hold Camus in the high esteem that I do, and the edition I possess has some excellent notes prepared by Jean Sarocchi): how does it stand on its own?

Well, with four and a hallf stars from me, it’s quite obvious that it stands very well. It stands and dances and plays a rugged round of golf.

Structurally, I’m quite sure that Camus would have made some changes if he had not moved away from the novel (it was first published in 1972, about 30 years after it had been dropped by its author, 12 years after his death). There are also some tonal incongruities.

But it is still delicious, and often simply lyrical to the point of some kind of divine atheistic hymn to the lack-of-God:

At the strange peace that filled him as he watched the evening suddenly freshening upon the sea, the first star slowly hardening in the sky, he realized that after this great tumult and this fury, what was dark and wrong within him was gone now, yielding to the clear water, transparent now, of a soul restored to kindness, to resolution.

Mersault is estranged by his rebellion against his human mediocrity, and he wants to occupy his happiness completely and authentically. Love has been a central pursuit for happiness, as it is for many people, in fact it is all he has, this pursuit of women that he recognizes as both vain and predatory. He reflects on making love with his ‘mistress’ Marthe that:

…this initial astonishment at possessing a lovely body, at mastering it and humiliating it. Now he knew he was not made for such love, but for the innocent and terrible love of the dark god he would henceforth serve.

And that is himself, completely, without the reflection of himself in others.

So he chases exile, he chases a greater depth of relationship, he chases authentic friendship, he chases total solitude, and in the end, can only find it in death:

Of that great ravaging energy which had borne him on, of that fugitive and generating poetry of life, nothing was left now but the transparent truth which is the opposite of poetry.

It is a perhaps a little more floral in its style to the style he would develop and become known for (notes indicate he was playing with Proust…) but it's beautiful and fantastic and happily happily tragic.

1

1

1

1